The Buddhist Principles

Refuge in 'The Three Jewels'

The three Jewels or the Triratna(in Sanskrit) or the Threefold Refuge are the three main components of the Buddhist creed. In Buddhism, the three jewels are the Buddha, the Dhamma(doctrine or law), and the Sangha (the monastic order, or community of believers). While on the path of becoming a Buddhist, one needs protection of the three jewels or the Three Refuge as they offer protection from the fickle and unstable world we live in.

The Buddha

In Buddhism, the lord Buddha is considered to be the prime source of inspiration and authority for adherents. The literal meaning of the word 'Buddha' means, awakened one, which also suggests that the enlightenment of the Buddha was a 'wake up' sign for the world with more zeal for light and enlightenment with an exemption from ignorance and delusion. In Theravada Buddhism, the Buddha is honoured as a special human being who, when confronted with the palpable suffering in the world and convinced that there had to be something more, sought and won enlightenment.

The Dhamma

The Dhamma refers to the code of conduct, or the doctrine. After the Buddha attained enlightenment, he had two options before Him - Either to keep the Divine knowledge of the truth to Himself, or to enlighten ever other beings, and not surprisingly, he opted for the later. The teachings propounded by the Buddha are known as the Dhamma in Pali or Dharma in Sanskrit language. The Dhamma comprises all the essential doctrines of Buddhism - The Four Noble Truths, Samsara, Karmaa, Rebirth or the cycle of birth and death etc. These teachings were first committed to writing in the Pali Canon in about the 1st century BCE.

The Sangha

Another jewel, the Sangha, a monastic community founded by the Buddha is highly revered. A Sangha gives special impetus to the monks and nuns as they make the Buddha's teachings the focus of their lives, devote their lives to meditation and welfare of other beings. They exemplify the Buddhist life par excellence providing example, guidance and inspiration to others as well.

The Four Noble Thruths

The Four Noble Truths are central key of the entire Buddhist teachings. Though easy to understand, its application grows richer and more profound as the practice grows further. The first noble truth is suffering, a condition that all living beings experience in various forms. The cause of suffering is craving or selfish desire. However, the third noble truth or Nirvana is a state which transcends all the sufferings. The fourth noble truth is the Noble Eightfold Path, the Buddha's teaching on the way to attain Nirvana. All these four noble truths are very practical and have everything to do with the present moment and how we relate to it.

Life means suffering.

One who has come to this earth is sure to pass through different stages of life, which includes happiness and sorrow, both. The world and the human nature - both are not perfect and therefore, to live means to suffer. During our lifetime, we have to endure different physical sufferings such as pain, sickness, injury, tiredness, old age, and eventually death; and we have to endure psychological sufferings like sadness, fear, frustration, disappointment, and depression as well. Although there are different degrees of sufferings and there are also positive experiences in life that we perceive on the other side of sufferings such as ease, comfort and happiness. But still, life on the whole is imperfect and incomplete, because our world is subject to impermanence. This further leads to the fact that we are unable to keep anything permanently that we long for; and just as happy moments pass by, we ourselves and our loved ones will pass away one day, too!

The origin of suffering is attachment.

The main cause of sufferings is attachment to transient things, which do not only include the physical surrounding objects but also our ideas, feelings and on the whole our perception. When we are attached to a particular thing or a person, we do not understand that these are temporary and are sure to depart from us one day or the other, and therefore, we ignore what is hidden in the future. The people and things we are passionate about and crave for, when part from us, we suffer!

The cessation of suffering is attainable.

The third noble truth or the Nirodha expresses the idea that sufferings can be eliminated by attaining dispassion. Nirodha extinguishes all forms of clinging and attachment. There is a simple way to end the sufferings - Remove the cause of the suffering, which every being can do by winning over his heart and mind. Nirvana, therefore, means freedom from all worries, troubles, complexes, fabrications and ideas.

The path to the cessation of suffering.

The path of Self-Control and self-Improvement gradually ends all the sufferings. The path, better known as the Eightfold Path is the middle way between the two extremes of excessive self-indulgence and excessive self-mortification, which further puts an end to the Cycle of Rebirth. The path that eliminates the sufferings and leads ones to 'moksha' can extend over many lifetimes, throughout which every individual's rebirth is subject to karmic conditioning. Every Craving, ignorance, delusions, and its effects are bound to disappear gradually as one moves on the path of self control.

Life means suffering.

One who has come to this earth is sure to pass through different stages of life, which includes happiness and sorrow, both. The world and the human nature - both are not perfect and therefore, to live means to suffer. During our lifetime, we have to endure different physical sufferings such as pain, sickness, injury, tiredness, old age, and eventually death; and we have to endure psychological sufferings like sadness, fear, frustration, disappointment, and depression as well. Although there are different degrees of sufferings and there are also positive experiences in life that we perceive on the other side of sufferings such as ease, comfort and happiness. But still, life on the whole is imperfect and incomplete, because our world is subject to impermanence. This further leads to the fact that we are unable to keep anything permanently that we long for; and just as happy moments pass by, we ourselves and our loved ones will pass away one day, too!

The origin of suffering is attachment.

The main cause of sufferings is attachment to transient things, which do not only include the physical surrounding objects but also our ideas, feelings and on the whole our perception. When we are attached to a particular thing or a person, we do not understand that these are temporary and are sure to depart from us one day or the other, and therefore, we ignore what is hidden in the future. The people and things we are passionate about and crave for, when part from us, we suffer!

The cessation of suffering is attainable.

The third noble truth or the Nirodha expresses the idea that sufferings can be eliminated by attaining dispassion. Nirodha extinguishes all forms of clinging and attachment. There is a simple way to end the sufferings - Remove the cause of the suffering, which every being can do by winning over his heart and mind. Nirvana, therefore, means freedom from all worries, troubles, complexes, fabrications and ideas.

The path to the cessation of suffering.

The path of Self-Control and self-Improvement gradually ends all the sufferings. The path, better known as the Eightfold Path is the middle way between the two extremes of excessive self-indulgence and excessive self-mortification, which further puts an end to the Cycle of Rebirth. The path that eliminates the sufferings and leads ones to 'moksha' can extend over many lifetimes, throughout which every individual's rebirth is subject to karmic conditioning. Every Craving, ignorance, delusions, and its effects are bound to disappear gradually as one moves on the path of self control.

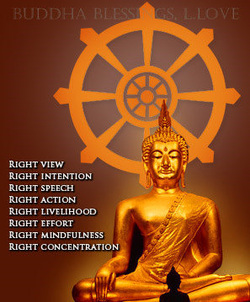

The Noble Eightfold Path

The Buddhist way of practice can better be described by the Noble Eightfold Path as it shows the way to the end of suffering. It was preached by Lord Buddha to his disciples. The Eightfold Path provides one a practical guideline to ethical and mental development by freeing the person from attachments and delusions, and thereby, paves way to the quest for truth. They are called noble because all these ways combine together to stand on the threshold of the noble or transcendent attainments.

The eight factors of the Noble Eightfold Path are as follows:

1. Right View.

2. Right Intention

3. Right Speech

4. Right Action

5. Right Livelihood

6. Right Effort

7. Right Mindfulness

8. Right Concentration

Right View

Right view is the beginning and the end of the path, it simply means to see and to understand things as they really are and to realise the Four Noble Truths. As such, right view is the cognitive aspect of wisdom. It means to see things through, to grasp the impermanent and imperfect nature of worldly objects and ideas, and to understand the law of karma and karmic conditioning. Right view is not necessarily an intellectual capacity, just as wisdom is not just a matter of intelligence. Instead, right view is attained, sustained, and enhanced through all capacities of mind. It begins with the intuitive insight that all beings are subject to suffering and it ends with complete understanding of the true nature of all things. Since our view of the world forms our thoughts and our actions, right view yields right thoughts and right actions.

Right Intention

While right view refers to the cognitive aspect of wisdom, right intention refers to the volitional aspect, i.e. the kind of mental energy that controls our actions. Right intention can be described best as commitment to ethical and mental self-improvement. Buddha distinguishes three types of right intentions:

1. the intention of renunciation, which means resistance to the pull of desire,

2. the intention of good will, meaning resistance to feelings of anger and aversion, and

3. the intention of harmlessness, meaning not to think or act cruelly, violently, or aggressively, and to develop compassion.

Right Speech

Right speech is the first principle of ethical conduct in the Eightfold Path. Ethical conduct is viewed as a guideline to moral discipline, which supports the other principles of the path. This aspect is not self-sufficient, however, essential, because mental purification can only be achieved through the cultivation of ethical conduct. The importance of speech in the context of Buddhist ethics is obvious: words can break or save lives, make enemies or friends, start war or create peace. Buddha explained right speech as follows:

1. to abstain from false speech, especially not to tell deliberate lies and not to speak deceitfully,

2. to abstain from slanderous speech and not to use words maliciously against others,

3. to abstain from harsh words that offend or hurt others, and

4. to abstain from idle chatter that lacks purpose or depth. Positively phrased, this means to tell the truth, to speak friendly, warm, and gently and to talk only when necessary.

Right Action

The second ethical principle, right action, involves the body as natural means of expression, as it refers to deeds that involve bodily actions. Unwholesome actions lead to unsound states of mind, while wholesome actions lead to sound states of mind. Again, the principle is explained in terms of abstinence: right action means

1. to abstain from harming sentient beings, especially to abstain from taking life (including suicide) and doing harm intentionally or deliquently,

2. to abstain from taking what is not given, which includes stealing, robbery, fraud, deceitfulness, and dishonesty, and

3. to abstain from sexual misconduct. Positively formulated, right action means to act kindly and compassionately, to be honest, to respect the belongings of others, and to keep sexual relationships harmless to others. Further details regarding the concrete meaning of right action can be found in the percepts.

Right Livelihood

Right livelihood means that one should earn one's living in a righteous way and that wealth should be gained legally and peacefully. The Buddha mentions four specific activities that harm other beings and that one should avoid for this reason:

1. Dealing in weapons,

2. Dealing in living beings (including raising animals for slaughter as well as slave trade and prostitution),

3. Working in meat production and butchery, and

4. Selling intoxicants and poisons, such as alcohol and drugs. Furthermore any other occupation that would violate the principles of right speech and right action should be avoided.

Right Effort

Right effort can be seen as a prerequisite for the other principles of the path. Without effort, which is in itself an act of will, nothing can be achieved, whereas misguided effort distracts the mind from its task, and confusion will be the consequence. Mental energy is the force behind right effort; it can occur in either wholesome or unwholesome states. The same type of energy that fuels desire, envy, aggression, and violence can on the other side fuel self-discipline, honesty, benevolence, and kindness. Right effort is detailed in four types of endeavors that rank in ascending order of perfection:

1. To prevent the arising of unarisen unwholesome states,

2. To abandon unwholesome states that have already arisen,

3. To arouse wholesome states that have not yet arisen, and

4. to maintain and perfect wholesome states already arisen.

Right Mindfulness

Right mindfulness is the controlled and perfected faculty of cognition. It is the mental ability to see things as they are, with clear consciousness. Usually, the cognitive process begins with an impression induced by perception, or by a thought, but then it does not stay with the mere impression. Instead, we almost always conceptualise sense impressions and thoughts immediately. We interpret them and set them in relation to other thoughts and experiences, which naturally go beyond the facts of the original impression. The mind then posits concepts, joins concepts into constructs, and weaves those constructs into complex interpretative schemes. All this happens only half consciously, and as a result, we often see things obscured. Right mindfulness is anchored in clear perception and it penetrates impressions without getting carried away. Right mindfulness enables us to be aware of the process of conceptualisation in a way that we actively observe and control the way our thoughts go.

Buddha accounted for this as the four foundations of mindfulness

1. Contemplation of the body,

2. Contemplation of feeling (repulsive, attractive, or neutral),

3. Contemplation of the state of mind, and

4. Contemplation of the phenomena.

Right Concentration

The eighth principle of the path, right concentration, refers to the development of a mental force that occurs in natural consciousness, although at a relatively low level of intensity, namely concentration. Concentration in this context is described as one-pointedness of mind, meaning a state where all mental faculties are unified and directed onto one particular object. Right concentration for the purpose of the Eightfold path means wholesome concentration, i.e. concentration on wholesome thoughts and actions. The Buddhist method of choice to develop right concentration is through the practice of meditation. The meditating mind focuses on a selected object. It first directs itself onto it, then sustains concentration, and finally intensifies concentration step by step. Through this practice it becomes natural to apply elevated levels concentration also in everyday situations.

The eight factors of the Noble Eightfold Path are as follows:

1. Right View.

2. Right Intention

3. Right Speech

4. Right Action

5. Right Livelihood

6. Right Effort

7. Right Mindfulness

8. Right Concentration

Right View

Right view is the beginning and the end of the path, it simply means to see and to understand things as they really are and to realise the Four Noble Truths. As such, right view is the cognitive aspect of wisdom. It means to see things through, to grasp the impermanent and imperfect nature of worldly objects and ideas, and to understand the law of karma and karmic conditioning. Right view is not necessarily an intellectual capacity, just as wisdom is not just a matter of intelligence. Instead, right view is attained, sustained, and enhanced through all capacities of mind. It begins with the intuitive insight that all beings are subject to suffering and it ends with complete understanding of the true nature of all things. Since our view of the world forms our thoughts and our actions, right view yields right thoughts and right actions.

Right Intention

While right view refers to the cognitive aspect of wisdom, right intention refers to the volitional aspect, i.e. the kind of mental energy that controls our actions. Right intention can be described best as commitment to ethical and mental self-improvement. Buddha distinguishes three types of right intentions:

1. the intention of renunciation, which means resistance to the pull of desire,

2. the intention of good will, meaning resistance to feelings of anger and aversion, and

3. the intention of harmlessness, meaning not to think or act cruelly, violently, or aggressively, and to develop compassion.

Right Speech

Right speech is the first principle of ethical conduct in the Eightfold Path. Ethical conduct is viewed as a guideline to moral discipline, which supports the other principles of the path. This aspect is not self-sufficient, however, essential, because mental purification can only be achieved through the cultivation of ethical conduct. The importance of speech in the context of Buddhist ethics is obvious: words can break or save lives, make enemies or friends, start war or create peace. Buddha explained right speech as follows:

1. to abstain from false speech, especially not to tell deliberate lies and not to speak deceitfully,

2. to abstain from slanderous speech and not to use words maliciously against others,

3. to abstain from harsh words that offend or hurt others, and

4. to abstain from idle chatter that lacks purpose or depth. Positively phrased, this means to tell the truth, to speak friendly, warm, and gently and to talk only when necessary.

Right Action

The second ethical principle, right action, involves the body as natural means of expression, as it refers to deeds that involve bodily actions. Unwholesome actions lead to unsound states of mind, while wholesome actions lead to sound states of mind. Again, the principle is explained in terms of abstinence: right action means

1. to abstain from harming sentient beings, especially to abstain from taking life (including suicide) and doing harm intentionally or deliquently,

2. to abstain from taking what is not given, which includes stealing, robbery, fraud, deceitfulness, and dishonesty, and

3. to abstain from sexual misconduct. Positively formulated, right action means to act kindly and compassionately, to be honest, to respect the belongings of others, and to keep sexual relationships harmless to others. Further details regarding the concrete meaning of right action can be found in the percepts.

Right Livelihood

Right livelihood means that one should earn one's living in a righteous way and that wealth should be gained legally and peacefully. The Buddha mentions four specific activities that harm other beings and that one should avoid for this reason:

1. Dealing in weapons,

2. Dealing in living beings (including raising animals for slaughter as well as slave trade and prostitution),

3. Working in meat production and butchery, and

4. Selling intoxicants and poisons, such as alcohol and drugs. Furthermore any other occupation that would violate the principles of right speech and right action should be avoided.

Right Effort

Right effort can be seen as a prerequisite for the other principles of the path. Without effort, which is in itself an act of will, nothing can be achieved, whereas misguided effort distracts the mind from its task, and confusion will be the consequence. Mental energy is the force behind right effort; it can occur in either wholesome or unwholesome states. The same type of energy that fuels desire, envy, aggression, and violence can on the other side fuel self-discipline, honesty, benevolence, and kindness. Right effort is detailed in four types of endeavors that rank in ascending order of perfection:

1. To prevent the arising of unarisen unwholesome states,

2. To abandon unwholesome states that have already arisen,

3. To arouse wholesome states that have not yet arisen, and

4. to maintain and perfect wholesome states already arisen.

Right Mindfulness

Right mindfulness is the controlled and perfected faculty of cognition. It is the mental ability to see things as they are, with clear consciousness. Usually, the cognitive process begins with an impression induced by perception, or by a thought, but then it does not stay with the mere impression. Instead, we almost always conceptualise sense impressions and thoughts immediately. We interpret them and set them in relation to other thoughts and experiences, which naturally go beyond the facts of the original impression. The mind then posits concepts, joins concepts into constructs, and weaves those constructs into complex interpretative schemes. All this happens only half consciously, and as a result, we often see things obscured. Right mindfulness is anchored in clear perception and it penetrates impressions without getting carried away. Right mindfulness enables us to be aware of the process of conceptualisation in a way that we actively observe and control the way our thoughts go.

Buddha accounted for this as the four foundations of mindfulness

1. Contemplation of the body,

2. Contemplation of feeling (repulsive, attractive, or neutral),

3. Contemplation of the state of mind, and

4. Contemplation of the phenomena.

Right Concentration

The eighth principle of the path, right concentration, refers to the development of a mental force that occurs in natural consciousness, although at a relatively low level of intensity, namely concentration. Concentration in this context is described as one-pointedness of mind, meaning a state where all mental faculties are unified and directed onto one particular object. Right concentration for the purpose of the Eightfold path means wholesome concentration, i.e. concentration on wholesome thoughts and actions. The Buddhist method of choice to develop right concentration is through the practice of meditation. The meditating mind focuses on a selected object. It first directs itself onto it, then sustains concentration, and finally intensifies concentration step by step. Through this practice it becomes natural to apply elevated levels concentration also in everyday situations.

The Five Precepts

The five precepts are also known as the Dhamma of the human beings as these are the moral conducts to make the human world bearable. The five precepts have been designed to restrain a Buddhist from making bad deeds in speech and body and to serve as the basis for further growth in the Dhamma.

The Five Precepts are as follows

1. Panatipata Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from destroying living creatures.

This precept applies to all living beings not just humans. All beings have a right to their lives and that right should be respected.

2. Adinnadana Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from taking that which is not given.

This precept goes further than mere stealing. One should avoid taking anything unless one can be sure that is intended that it is for you.

3. Kamesu Micchacara Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from sexual misconduct.

This precept is often mistranslated or misinterpreted as relating only to sexual misconduct but it covers any overindulgence in any sensual pleasure such as gluttony as well as misconduct of a sexual nature.

4. Musavada Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from incorrect speech.

As well as avoiding lying and deceiving, this precept covers slander as well as speech which is not beneficial to the welfare of others.

5. Suramerayamajja Pamadatthana Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from intoxicating drinks and drugs which lead to carelessness.

This precept is in a special category as it does not infer any intrinsic evil in, say, alcohol itself but indulgence in such a substance could be the cause of breaking the other four precepts.

Additional Precepts

Besides the major five precepts, there are other important precepts as well for a Buddhist. On special holy days, there are three precepts followed by the Buddhists, mainly of the Theravada tradition :

1. To abstain from taking food at inappropriate times.

This means following the tradition of Theravadin monks and not eating from noon one day until the sunrise of the next day.

2. To abstain from dancing, singing, music and entertainment as well as refraining from the use of ornaments, perfumes and other items used to beautify the person.

3. To undertake the training to abstain from using high or luxurious beds.

This rule is regularly adopted by members of the Sangha aand followed by a lay person on special occasions.

The Five Precepts are as follows

1. Panatipata Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from destroying living creatures.

This precept applies to all living beings not just humans. All beings have a right to their lives and that right should be respected.

2. Adinnadana Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from taking that which is not given.

This precept goes further than mere stealing. One should avoid taking anything unless one can be sure that is intended that it is for you.

3. Kamesu Micchacara Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from sexual misconduct.

This precept is often mistranslated or misinterpreted as relating only to sexual misconduct but it covers any overindulgence in any sensual pleasure such as gluttony as well as misconduct of a sexual nature.

4. Musavada Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from incorrect speech.

As well as avoiding lying and deceiving, this precept covers slander as well as speech which is not beneficial to the welfare of others.

5. Suramerayamajja Pamadatthana Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami

I undertake the precept to refrain from intoxicating drinks and drugs which lead to carelessness.

This precept is in a special category as it does not infer any intrinsic evil in, say, alcohol itself but indulgence in such a substance could be the cause of breaking the other four precepts.

Additional Precepts

Besides the major five precepts, there are other important precepts as well for a Buddhist. On special holy days, there are three precepts followed by the Buddhists, mainly of the Theravada tradition :

1. To abstain from taking food at inappropriate times.

This means following the tradition of Theravadin monks and not eating from noon one day until the sunrise of the next day.

2. To abstain from dancing, singing, music and entertainment as well as refraining from the use of ornaments, perfumes and other items used to beautify the person.

3. To undertake the training to abstain from using high or luxurious beds.

This rule is regularly adopted by members of the Sangha aand followed by a lay person on special occasions.

The Three Marks of Existence

After having a lot of contemplation on the spiritual matters, Lord Buddha came to a conclusion that everything in this physical world is marked by three characteristics, known as the Dharma Seals or the three characteristics of existence or Ti-Lakkhana in Pali. These three marks of conditioned existence are Anatta, Anicca and Dukkha.

Anatta

Anatta (a Pali word) or Anatman (a Sanskrit word) is basically the concept of a self or Atman or soul. This concept refers to an unchanging, permanent and static essence conceived by the virtue of existence. But the Buddha rejected the permanent concept of Atman and its relation with Brahma, the Vedantic monistic ideal. Instead, He emphasised on the changing character of the soul and preached that all the concepts of a substantial self were not correct and formed because of ignorance.

Anicca

Anicca or Anitva means that nothing is constant. All the things, feelings and experiences are inconsistent and impermanent. There is no such thing that lasts forever.

Dukkha

When we fail to grasp the first two conditions truly, we suffer and that suffering is known as Dukkha. We always crave for permanent satisfaction, but forget that nothing lasts not even satisfaction. Therefore, it is all about realisation, which can prevent us from Dukkha and not only Dukkha, but other two marks and their sufferings can also be eliminated by driving away ignorance.

Anatta

Anatta (a Pali word) or Anatman (a Sanskrit word) is basically the concept of a self or Atman or soul. This concept refers to an unchanging, permanent and static essence conceived by the virtue of existence. But the Buddha rejected the permanent concept of Atman and its relation with Brahma, the Vedantic monistic ideal. Instead, He emphasised on the changing character of the soul and preached that all the concepts of a substantial self were not correct and formed because of ignorance.

Anicca

Anicca or Anitva means that nothing is constant. All the things, feelings and experiences are inconsistent and impermanent. There is no such thing that lasts forever.

Dukkha

When we fail to grasp the first two conditions truly, we suffer and that suffering is known as Dukkha. We always crave for permanent satisfaction, but forget that nothing lasts not even satisfaction. Therefore, it is all about realisation, which can prevent us from Dukkha and not only Dukkha, but other two marks and their sufferings can also be eliminated by driving away ignorance.

Other Principles and Practises

The concept of Buddhism includes various principles necessary to attain the path of enlightenment or to become a Buddhist. Besides the Eightfold Path, Five Percepts and Four Noble Truths, there are numerous other principles for a Buddhist to follow such as meditation, karma and rebirth.

Meditation or dhyana is a common practice in all the schools of Buddhism, which aims at concentration and freeing the mind from desires.

The law of karma is another Buddhist doctrine and practice which happens within the dynamic of dependent organisation, Pratitya-Samutpada. Those actions which give positive result are known as good while those which deliver negative results are considered to be unskillful or bad actions. However, both of them are expressed by the way of mind, body or speech. There are many actions which bring instant retribution though there are others that may not appear until a future lifetime. Therefore, what one should do is to work positively towards elimination of their sufferings.

The third principle of Rebirth is closely related to the second one, the law of karma, which is more or less about as you sow, so shall you reap. In other words, actions of the past life has an effect in the present one, and likewise, actions of the present life would decide your future life, thus making a chain of existence. An action in this life may not give fruit or reaction until the next life time. But, this cycle of birth and death can only be broken by the full realisation of the absence of an eternal self or soul or 'atman'.

Meditation or dhyana is a common practice in all the schools of Buddhism, which aims at concentration and freeing the mind from desires.

The law of karma is another Buddhist doctrine and practice which happens within the dynamic of dependent organisation, Pratitya-Samutpada. Those actions which give positive result are known as good while those which deliver negative results are considered to be unskillful or bad actions. However, both of them are expressed by the way of mind, body or speech. There are many actions which bring instant retribution though there are others that may not appear until a future lifetime. Therefore, what one should do is to work positively towards elimination of their sufferings.

The third principle of Rebirth is closely related to the second one, the law of karma, which is more or less about as you sow, so shall you reap. In other words, actions of the past life has an effect in the present one, and likewise, actions of the present life would decide your future life, thus making a chain of existence. An action in this life may not give fruit or reaction until the next life time. But, this cycle of birth and death can only be broken by the full realisation of the absence of an eternal self or soul or 'atman'.